'A Close Call at West Baltimore'

[This article was published in the September 2004 issue of the Bull Sheet]

It has been my intention from time to time to relate various experiences from my career on the railroad. Most have been happy ones. This one, however, is one I wish had not happened. It is the sort of thing that bad dreams are made of.

It happened in the fall of 1975. It was a Thursday. I was assigned to second-shift at HX Tower at Halethorpe, near Baltimore. I reported to work at the usual time.

As part of my transfer with the first-shift operator, I was told that eastbound train Baltimore-96 was on No.4 track at West Baltimore. The train had already coupled to its rear block of cars for Bay View, and its crew had been instructed to operate through Mount Winans Yard toward CX Tower where the train would continue on to its destination.

But herein I should dwell a bit and explain some things in order that you can better understand the developments that followed:

Remember, this was nearly 29 years ago. Trains still had cabooses; trains still had four-person crews. Two-way radios - although many other railroads used them - had not been formally introduced to road trains on the B&O. Some crews did use their own CB radios, albeit unofficially, but radios were not yet available in the towers or in the dispatchers' offices. My tower had antique telephones for use in talking with the dispatchers, the yardmasters, and crews who would call us from phone boxes scattered in strategic places along the right of way. If we had anything to communicate to a moving train, we did it the old fashioned way using a train order stick. Hand signals were the norm, too, and if an emergency arose and we needed a train to stop, we would flag the train using a lighted fusee, red flag, or anything swung in a horizontal direction. Sticking brakes were indicated by rubbing the palms of the hands.

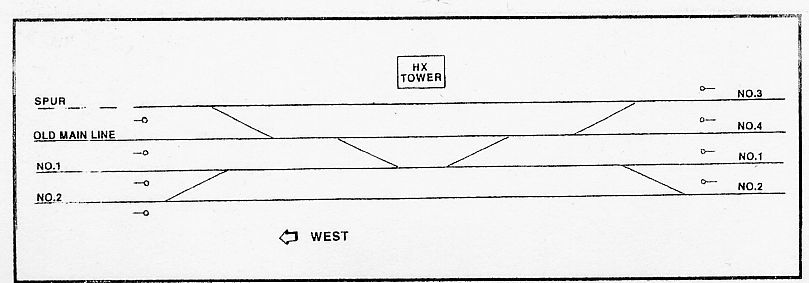

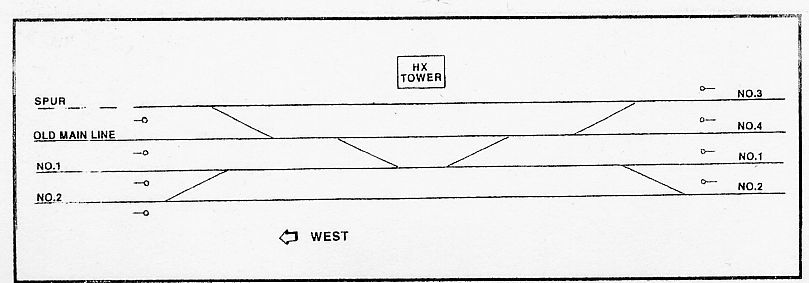

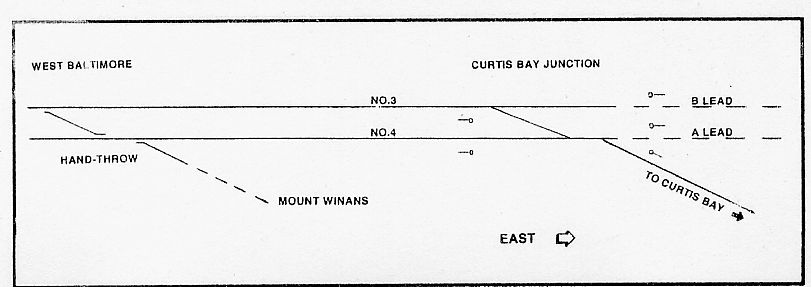

The operator at HX Tower controlled six crossovers and eight signals at its interlocking, the number needed to effect moves connecting four tracks running east and west, directly in front of the tower. In addition, one power crossover and one switch were remotely controlled from HX Tower at a location known as Curtis Bay Junction, three miles to the east (see diagrams). The tracks numbered 3 and 4 respectively were the same tracks at and between both locations. Both tracks had bidirectional signaling. A code-type model board was in place at HX Tower for the operator to control the switches and signals at Curtis Bay Junction. East of Curtis Bay Junction were three tracks - one to Curtis Bay (which became two tracks a short distance further east), and two tracks into the yard at Mount Clare. The yard tracks were designated B Lead (a tangent extension of No. 3 track) and A Lead (a tangent extension of No. 4 track). References to these tracks were often used interchangeably - B lead as No. 3 track, A lead as No. 4 track - but properly their names changed at the junction.

Another important distinction to be made regarding these two tracks is the manner in which movements were supervised on either side of Curtis Bay Junction. Numbers 3 and 4 tracks west of the junction were supervised by the train dispatcher; B and A leads east of the junction were supervised by the yardmaster at Mount Clare. While the operator served as the eyes and ears of both the train dispatcher and the yardmaster, and the operator did control the switches and signals into each of the others' territory, he did not "supervise" those movements. Indeed, he merely did what he was told.

There were some locations on the railroad where tower operators in fact did have supervision of tracks, but this was not the situation at any of the locations under the HX Tower operator's control. It is important, therefore, not to confuse the word "supervise" with the word "control." They have different meanings.

About half a mile west of Curtis Bay Junction (two and one-half miles east of HX Tower) was a location known as West Baltimore. Here there was a hand-throw crossover between Nos. 3 and 4 tracks, and a switch off No. 4 track into Mount Winans Yard. The tracks in Mount Winans Yard were supervised by the train dispatcher, and his permission was required before any trains used that yard or operated and/or used either the crossover or switch at West Baltimore.

I settled in that afternoon for another day of work. Before the first-shift operator left, he told me that eastbound train Baltimorean would be showing up shortly. Both Baltimore-96 and Baltimorean had similar working agendas. Both typically had a block on the head end for Curtis Bay, a block in the middle for Mount Clare, and a block on the rear for Bay View. The crews would already have instructions from their originating point, including cut numbers, and they would know to stop their train at West Baltimore where they would cut behind their last Curtis Bay car and take that block of cars to Curtis Bay. Signal indication governed at Curtis Bay Junction, and it was the operator's responsibility to control the move as authorized by the train dispatcher. Once the head cut of cars had cleared the switches at Curtis Bay Junction, a yard engine from Mount Clare would come out onto the track the train was on, couple to the middle block of cars, and take those cars into Mount Clare. Later, the engine of the train that had taken the head end to Curtis Bay would return to couple to its rear block of cars at West Baltimore. The train would then operate either through Mount Winans (as decided by the train dispatcher) or (if permitted by the yardmaster) through Mount Clare toward CX Tower where the train would continue on to its destination. The preferred route was through Mount Winans, but it was not uncommon to operate through Mount Clare instead.

As to Baltimore-96, which was still on No. 4 track at West Baltimore, the crew had already been instructed to go through Mount Winans.

I then heard a ring on the block phone line. Actually, it was one of several block lines that served HX Tower. Each was wired to a different bell, and operators could tell by the tone of the bell which line was ringing. In fact, the operator could even tell by its resonance whether the ring was from a hand crank or an electric ringer. This particular ring was from the block line that served the area of West Baltimore and Mount Winans (we called it the "Mount Winans line"). It was rung with a hand crank, and this further indicated that the caller was using a wayside call box and was not calling from someplace that had the modern convenience of electricity. The call was not directed to me, but using the ring code of two shorts I could tell it was directed to the yardmaster at Mount Clare. I listened in.

Eavesdropping on block line calls was commonplace. The line was, after all, for use of official business. It functioned as a party line throughout its geographic system, and a call intended for one office or individual might be of benefit to others, if only as a means of knowing what's going on. The call was from a crew member of the Baltimore-96 (which was the only train in the vicinity of West Baltimore at the time)...

The crew member inquired of the yardmaster if it would be possible for their train to operate through Mount Clare rather than Mount Winans. It was payday, and members whose checks were distributed at Mount Clare wanted to pick them up as they came through rather than drive there after they finished their assignment at another location later that evening. This was a reasonable request, of course, but it is bewildering that they did not think of this when they were earlier instructed to operate through Mount Winans.

The yardmaster (who knew that the train was on No. 4 track) replied that A lead was blocked. If they wanted to come through Mount Clare, they would have to come in B lead from Curtis Bay Junction.

Note once again the diagrams shown above... The train was on No. 4 track. The only power-operated switch that I controlled at Curtis Bay Junction was oriented in the wrong direction for a train to proceed eastward on No. 4 track into Mount Clare on B lead. A train, if short enough to fit between the hand-throw crossover at West Baltimore and the eastward signal at Curtis Bay Junction, could make a backup move through the hand-throw crossover onto No. 3 track and then proceed east on B lead. Or it could proceed east on No. 4 track to Curtis Bay Junction and toward Curtis Bay far enough to clear the junction, and I could then reverse the power crossover and give the train the signal to back onto No. 3 track at that location. Either move would require the permission of the train dispatcher (obtained from me after I asked him). But all this became a moot point, as things developed; the Baltimorean came on the bell (our expression to describe the train entering the tower's approach circuit), and it was routed eastward onto No. 3 track at HX Tower.

The Baltimore-96 already had its instruction to operate through Mount Winans, and any subsequent request to use No. 3 track to reach B lead instead would simply be denied. Anyway, no such request was made.

But herein developed something that would have prevented any further communication with the Baltimore-96 anyhow. About the time the discussion between the crew member of the Baltimore-96 and the yardmaster was completed, the block line became very noisy. This was an antique system with many phones - a number of which were exposed to the elements - connected to a single line, and a loose or exposed wire at any of its locations could inflict the line with a humming sound. Sometimes we could talk in spite of the sound; sometimes we could not. In this particular instance, the line was so badly shorted that it was of no further use until it could be repaired. Each tower had a patch board by which portions of a line could be isolated from others, and this could sometimes remedy the problem. But since my tower was at the end of the same circuit as the wayside phone as had been used initially, there was no immediate solution to restore service by this method. The line was too noisy, and it stayed that way. If the crew of the Baltimore-96 had attempted to call the tower, they would not have been able to get through.

I then devoted my attention to the progress of the Baltimorean. By now it had passed its distant signal at Elkridge with (presumably) an approach-medium aspect, and was within sight on No. 2 track along the mile-long tangent section between Saint Denis and the eastward home signal to the tower, there having (again, presumably) a medium-approach aspect to cross over through the interlocking onto No. 3 track. I was watching this from my desk, instinctively keeping an eye toward the interlocking model board which hung directly above the opened window at the west side of the building through which I could see the train as it approached. With no other business to attend to at this moment, it was my style in such instances to wait until the engine had actually entered the interlocking before I went outside to watch it pass. In fact, I had learned to time my descent to the ground to coincide with the passing of the engine, usually coming to a halt at the threshold of the boardwalk leading to the tracks just at that precise instant. I sort of made a game of it!

About a second before the Baltimorean passed beneath the signal bridge, I noticed with alarm that all of my track circuit lights on No. 3 track between HX and Curtis Bay Junction came on. This would (or should) have caused the eastward home signal to drop to an all-red aspect. Had the crew on the Baltimorean seen the signal change in this fashion, they would have taken immediate action to bring their train to a stop. However, I was not sure if they had actually seen this happen. There may have been a micro-second of reaction for the signal relays to change the aspect to red following the dropping of the circuit, or more realistically it was probable that the engine had passed the point where the crew could still see the signal, and they would not have seen it change to red.

The dropping of the circuit might not have caused me such alarm except for an instantaneous suspicion that (maybe) the hand-throw crossover at West Baltimore was being thrown. A quick glance at the circuits on No. 4 track revealed that that track was still occupied. Uh-oh! I could only imagine what was happening at West Baltimore. My worst conclusion was that the Baltimore-96 might be backing over onto No. 3 track - westward - at the same time that the Baltimorean was routed onto the same track - eastward. And there were no further signals that the Baltimorean would encounter eastward on No. 3 track to protect them from such a move.

By now the Baltimorean was entering the interlocking, and it showed no signs of coming to a stop. Quickly (very quickly) I grabbed the red flag which was kept for contingencies next to the door, and I ran down the steps and out onto the boardwalk, frantically waving the train to a stop. The train stopped about 400 feet east of the tower. Indeed, it was stretched through my entire interlocking.

The conductor walked back and I met him half way. I told him that I thought something was remiss at West Baltimore, and I told him not to move his train until I learned something.

After I caught my breath, I went back up into the tower and told the dispatcher that I had flagged the Baltimorean. I shared with him what I suspected might be going on at West Baltimore. In short order my circuits on No. 4 track went out. This meant that the Baltimore-96 was no longer on No. 4 track. However, the circuits on No. 3 track were still on. The block line was still noisy, and I was unable to make contact with the yardmaster at Mount Clare. (HX, at the time, had no "regular" phone, such as could be used to dial numbers to the outside world. Again, this was still old-time railroading!)

The train dispatcher (who did have a regular phone) made contact with the yardmaster directly, and it was eventually confirmed that the Baltimore-96 had indeed backed over onto No. 3 track, and then proceeded east to Curtis Bay Junction, was standing at the eastward signal, and the yardmaster had said it was OK to give the train the signal to proceed into the yard on B lead.

At this point, do not be confused over division of supervision. It was the yardmaster's decision that permitted me to code the signal into his yard. The train dispatcher was only relaying the information to me because I had no communication with the yardmaster directly. Once the Baltimore-96 cleared into the yard on B lead, and the circuits on No. 3 track cleared, I told the crew of the Baltimorean to proceed east once again (which, by rule, would be at restricted speed in this instance).

At issue, of course, was why the crew of the Baltimore-96 had disregarded proper procedures by backing their train over onto No. 3 track. The following week, a formal investigation was held. I was called as a witness.

I had never been to a formal investigation. In fact, this proved to be the only one I would ever have to attend. No sorrow over that!

The investigation was held in one of the offices on the second floor of Camden Station. Formality was more an order of the day back in 1975 than it would be today, and I showed up in a necktie, as did the others who were called. The investigation was conducted by an assistant trainmaster. The four members of the crew of the Baltimore-96 - conductor, engineer, brakeman and flagman - all of whom had been charged with responsibility in the incident, were there, along with designated representatives from their respective unions to which they belonged. I was there merely as a witness; I needed no representative.

The proceedings were recorded by a "typist." The gal was not a stenographer - or perhaps taking shorthand was not allowed - but she recorded everything using a manual typewriter! (Remember them?) As something was said, the typist would go to work and try to keep up. Ha! This meant that only about a dozen words could be said before whoever was speaking had to stop... The typist would go pecka-pecka-pecka-pecka-peck for a while, then when she stopped, the person speaking could continue. Old time railroading at its best! The procedure, however, did allow somebody to think through what he would say next, and a real-time record of the proceedings was available as things progressed.

A few statements were taken, but it did not take very long before the proceedings came to an abrupt halt. Representatives for the four crew members raised an objection because the yardmaster involved had not been called as a witness. Indeed, it might even be argued that he should have been charged with responsibility - if it could be shown that he had implied that permission had been granted for the train to cross over in dispatcher-supervised territory. The yardmaster was not charged, but the investigation was adjourned for several days in order that he could attend as a witness.

The second portion of the investigation was held, this time in an office on the third floor of Camden Station. Oh yes, did I mention that I had to attend both portions of the investigation on my own time? I could not be paid for attending it, even as a witness, unless it was during my regular duty hours!

Each of those involved in the incident was questioned by the investigating officer. Rules that had allegedly been abridged were quoted, and those who had been charged with responsibility were asked to clarify whether or not they had complied with those rules.

It was quickly determined that the crew member who had made the call to the yardmaster to ask if it would be possible for the train to operate through Mount Clare, rather than Mount Winans, was the train's brakeman. He, in turn, had told his engineer and conductor that it was OK for the train to back over onto No. 3 track in order to get into position to go through Mount Clare using B lead. The fact that the engineer and conductor had taken this information - which affected the movement of their train - from the brakeman was in itself a violation. Brakemen were not permitted to do this. While brakemen could use the phone for informational purposes, or emergencies, only the conductor or engineer were allowed to secure instructions or to obtain permission that affected their operations. This was the case regardless of who supervised the tracks involved.

The conductor was a quiet sort of fellow who lent the impression that he could gracefully accept the consequences of his action. He was a real gentleman. The engineer, by contrast, was a rather cantankerous hard-liner who insisted that it was perfectly all right for him to accept operating instructions obtained through his brakeman, in the engineer's words, "as my representative." Repeatedly the investigating officer quoted the rule involved, even asking the engineer to read it out loud, and the engineer still maintained that his use of the brakeman for this purpose was in compliance.

All the while, the investigation proceeded at a snail's pace, owing to the slow process involved with the typing of the transcript.

When it was my turn to be questioned, I opened by reading a statement I had drafted in advance of the investigation. I had even made copies of it which I distributed to those who were present. Since the typist was also given a copy, I did not have to wait for her to catch up. She merely typed my statement into the transcript using the copy of it I had given her, and I rattled on without interruption. It was my intention to present all the facts as I knew them without the need to answer a zillion questions afterward.

There were some questions, though - some rather inane. "Was it possible for a train to use the crossovers at West Baltimore without permission?" the brakeman asked. Why had I given the Baltimorean the signal to proceed onto No. 3 track in the first place, since I knew the Baltimore-96 was on No. 4 track and might want to use B lead? the engineer asked. To this latter question I explained the protocol for obtaining permission to make main track moves at West Baltimore and how it was everyone's duty to follow the rules wherever they applied. His crew never had permission to use No. 3 track. Anyway, the Baltimore-96 had already been instructed to use Mount Winans, and those instructions were still in effect at the time.

The pace of the investigation moved slowly, and we took a break for lunch. We returned an hour later, but the typist was late arriving. Since the investigation could not proceed until she got back, the time was spent in railroad banter. The engineer, now in a more jovial mood than he had been earlier, recounted running Budd cars out of Washington en route to Baltimore. Sometimes his train would pass New York Avenue at the same time a Pennsy train with a GG1 would be moving along side in the same direction. Those sleek GG1's had some great power, he said, and they would always pull ahead of the Budd cars once the trains reached Ivy City and accelerated.

There was a table next to my chair, and I piled upon it the contents of several rolls of half dollars I had gotten at a bank during my lunch break. To one pile went the coins from the 1960's, to another went the coins from the 1970's. This effectively separated the silver-clad coins from those minted without silver. I explained the significance to those who were curious - how the silver-clad halves had added value (then about 15 cents) above their face value due to their silver content. (Halves minted before 1965 were worth even more.)

The typist got back about half an hour late, and the proceedings began once again. About a dozen words would be spoken, and then it was pecka-pecka-pecka-pecka-peck once again until she caught up. The whole affair took about six hours altogether; a more efficient system of might have cut it by two thirds.

With the investigation concluded, the matter was referred to the superintendent and division manager for recommendations, and then sent to the regional manager for a decision. It was concluded that the conductor, engineer and brakeman were at fault for violating the rule requiring that only the conductor or engineer obtain instructions about operating their train, for making a crossover move without securing permission from the train dispatcher, and for creating an unsafe situation. The flagman, who had thrown the crossover switches involved, was exonerated. He was merely following the instruction of his conductor, and had no reason to believe that the instruction was improper. The three crew members who were found at fault were awarded 30-days of suspension.

Many times I have thought about the situation and pondered what might have happened had the Baltimorean gotten by my station without being flagged to a stop. Indeed, if the Baltimorean had shown up just 15 seconds sooner, that is exactly what would have happened. Would there have been a collision? Remember, there were no further signals to be seen.

Just west of West Baltimore - where the trains would have encountered each other - there were four main tracks (Nos. 1 and 2 tracks continued to parallel Nos. 3 and 4 to this area before geographically splitting away). It is in a deep cut, but the tracks were tangent for about a quarter of a mile from a curve where first sight would have been encountered. From a distance it may have been difficult to tell which track the other train was on. Still, with a maximum speed of 20 miles per hour, I feel it is likely that the two trains could have - and would have - stopped in time. But it would have been a close call!

A year or two later, track and signal changes were implemented at West Baltimore. The hand-throw crossover between Nos. 3 and 4 tracks was replaced with a power crossover afforded with signal protection. The incident as described above could no longer happen.

-- Allen Brougham

.