September 1995

East Norwood Tower Closes

CSXT's East Norwood Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio, has been

retired.

CSXT Automotive Train to Lose Long-Standing Designation

Over a quarter of a century ago the B&O designated

its premier automotive train as 396. This number was carried through the

Chessie years and into the CSX-era. In recent years it was given an alpha-prefix

- first R and later Q - but the number remained. Now it appears that the

designation for that particular train will vanish. Under a proposal to

group all CSX automotive trains into the Q200 series, Q396 is slated to

become Q286.

CSXT to Redesignate Non-Automotive Trains of 200-Series

As part of the plan to group CSX automotive trains into

the Q200 series, non-automotive trains with R or Q designations in the

200 series will be redesignated. R250, the Orange Juice Train, is slated

to become K450; and R280, the Trash Train, is slated to become K502.

CSXT Adopts Service Lane Title

CSXT has adopted the title "Service Lane" to

some key corridors. The first of these was the Chicago-Nashville corridor.

Now comes the Florence Service Lane, with implementation of new service

design responsibilities slated to begin later this month. As part of the

plan, the RF&P Subdivision is slated once again to become a part of

the Baltimore Division.

CSXT Seeks Employee Help in Finding Idle Locomotives

CSXT has a locomotive awareness team made up of people

from all operating departments. They are attempting to find under-utilized

locomotives to handle the annual business peak this fall, thus helping

to avoid the need to lease units from other companies. One way to find

locomotives is to ask the rank-and-file employees to look for them. A recent

issue of CSXT's Midweek Report, distributed to all employees by computer,

has asked for everyone's help in finding at least 100 locomotives having

the potential to spend more of their time pulling freight.

Jim Collins Dies

[Reported by Allen Brougham] . . . Retired B&O train dispatcher

Charles Nelson Collins Jr. died on July 27. He was 68. Known as Jim by

his co-workers, he was also sometimes called Chuckie. I also called him

by the name of "Snick," a phonetic pronunciation of his initials

CNC used on train orders. He retired as a train dispatcher in early 1988.

His position at the time was daylight "ML" dispatcher, with territory

between Halethorpe and Brunswick, Maryland. This was before the consolidation

of dispatchers in Jacksonville, Florida, and Jim's office was then at Halethorpe.

He was one of the first to serve at the Halethorpe facility when functions

were transferred from Camden Station in Baltimore. Prior to becoming a

dispatcher a number of years earlier, he had been an operator at towers

in the Brunswick, Maryland, area, including the Old Main Line and Metropolitan

subdivisions. Jim is remembered as a conscientious worker having an on-going

sense of humor. "Don't hold 'em, roll 'em!" he would often say.

His off-hand remarks about events that were happening, even under pressure,

lent spirit to those with whom he worked. In the early 1970s, I often served

as sidewire operator in the Camden Station office, a job which included

the duty of reporting train delays. On asking Jim for assistance in explaining

a particular delay, he often replied: "Just write down 'insufficient

time in schedule for move that was made!' " One can wonder the reaction

transportation officials would have had if I were to report such an ambiguous

delay, but this was the type of humor for which Jim was noted. He lived

in Frederick, Maryland, and he kept in contact with a number of his co-workers

after he retired. He is survived by two sons, a sister, and a grandson.

His wife preceded him in death.

Caboose Man Steam-Cleans His Fleet

[Reported by Allen Brougham] . . . Don Stewart, the Caboose Man

of Hyndman, Pennsylvania, on the route of the Capitol Limited, decided

recently that road grime, rust and oxidation had taken their toll on his

noted collection of C&O cabooses. So he had them cleaned. The scrub-down

took place on August 4. To do the job he contracted the Magiclean Company

of Salisbury, Pennsylvania, and a crew of three with their specially equipped

truck of chemical tanks and compressors took eight hours to prepare, wash,

and rinse both cars. He reports the process removed all road grime and

rust, and made them look almost as if they had just been painted. Rust

spots will now be primed with yellow primer, and repainting is scheduled

for this fall. "The oxidation that plagued the 903556 has all been

removed and it shines again," he says, "and the 904115 has sprung

back to bright life, too," Don, of College Park, Maryland, is a retired

meteorologist. He knows what the atmosphere can do to things such as cabooses.

Even in the clean air of the mountains things can happen, and the residue

from passing trains doesn't help, either.

He purchased his first caboose - the one with the cupola - in June of

1990. He placed it on a section of track on a two-acre plot of land he

leased from the railroad, just off the route of a one-time interchange

track that had connected the B&O with a non-abandoned Pennsy line.

He then began using the car as a retreat, to relax and enjoy the solitude,

and to share time with his many neighbors. Two years later he bought the

bay window caboose. [See Bull Sheet of May 1993.]

Don was recently featured in a front page story in a newspaper published

by the Hyndman-Londonderry Library. It's the type of paper that publishes

news about high school homecomings, weddings, and citizens' vegetable gardens.

And as to Don, the story reports that he had just donated the book Sand

Patch - Clash of the Titans to the library. "If you haven't read

it, make it a must on your reading list," went the story. It also

described how Don had chosen Hyndman for his caboose site. It was "because

the people are friendly and accepted me with no questions." To the

folks of Hyndman, this is front page news!

A New Atlas for Railfans

Railfans have historically relied on maps to help

them ferret out locations. But now there's a map that goes a bit further

-- it shows how busy a line is. It's the U.S. Railroad Traffic Atlas,

published by Ladd Publications, a 98-page softbound on quality stock showing

virtually every railroad in the country -- even Hawaii. Harry Ladd, with

a degree in geography and an interest in trains, is surely living the best

of both worlds by presenting this atlas. It updates an earlier hand-drawn

version by employing the modern benefits of a computer. Each rail corridor

is keyed by density with the busiest lines the boldest. There are seven

categories, each determined by tonnage. These are not topo maps, and there

are no highways juxtaposed with the rail lines. What you have, then, is

a map showing only railroads - with emphasis on which are the busiest.

Maps are included for each state - or clusters of states - and there are

also system maps for 14 major railroads. (The system map for Amtrak is

keyed to frequency rather than tonnage.) The U.S. Railroad Atlas will be

a valuable tool to those in the field; also to those riding Amtrak who

can quickly identify adjoining or adjacent lines en route. (Allow some

orientation time to study the symbols and instructions; they read like

a tax form.) The atlas lists for $27. For further information write Ladd

Publications, P.O. Box 1671, Orange, California 92668-0671.

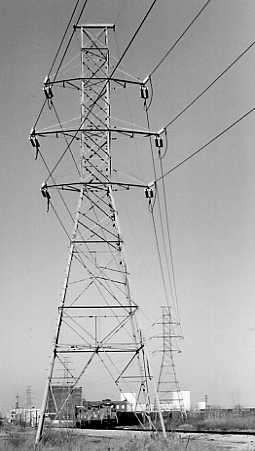

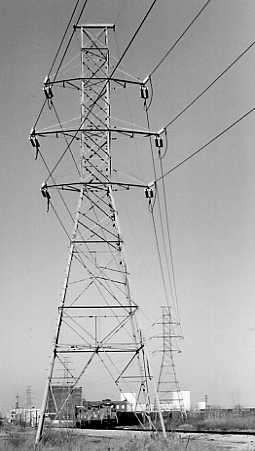

Those Mighty Power Lines

[By Allen Brougham] . . . OK, this is not

your typical Bull Sheet article. But a little while back I made myself

a promise to some day write about another interest of mine. Anyway, trains

can get a bit monotonous. I've always admired the big transmission lines.

As a kid I called them High Violence Lines (misreading the word "voltage"),

but somehow the name seems to fit. Once, when I was about 12 and visiting

a relative, I stood in his field having a big power line and stared in

awe at the 12-story-high lattice towers holding the lines. I thought they

were neat. My interest became dormant, of sorts, until about three years

ago when I saw a sketch depicting a huge transmission line being planned

in Pennsylvania which would have crossed the East Broad Top several times.

While I had sympathy for the cause that the line not scar the landscape,

I'll have to admit that I had some feelings that I wanted to see it built.

It wasn't. But someday it might be. This line, of the 500-kilovolt variety,

would be part of the interconnecting "grid," the type neighboring

utility companies use for trading power. Like it or not, these systems

are essential. In fact, the infamous 1965 power outage in New York and

New England, lasting several hours, was mostly blamed on the failure of

the grid in a time of need. A couple of years ago I met a railfanning gent

who happened to be a retired load dispatcher. We spent several hours talking

-- not about trains, but about his company's transmission system. He later

got for me a map showing the nationwide interconnector network. No dinky

lines on this map - just those of 230-kV or greater. What a treat! Occasionally

I've made short-distance trips to research just where some of the big power

lines go, and to see what happens when they meet up with other biggies.

Then, on my 1994 Amtrak adventure to Montana, I kept a sharp lookout for

transmission lines along the way. (You ought to see some I saw in Minnesota!)

Then several months ago I came across an interesting "find" in

northern Baltimore County. There, embedded in the trees, was a retired

line - just the lattice towers remaining - the result of an apparent rerouting

to increase capacity. This, to me, was as exciting as finding a long-lost

and rusting locomotive!

When you think of it, power lines and railroads have a lot in common.

Both use a narrow right-of-way over a great distance, and both involve

transportation. Then, too, many exist side by side. I'm not advocating

the formation of a power line club, and it's not my intention to transform

(no pun intended) the Bull Sheet into a power line publication. But it

would be interesting to see if any readers share this particular interest.

But if you don't share my interest, please don't ask me to explain it.

If you do, I'll simply ask you to explain your interest in trains

.....

Story by Allen Brougham... Photo of power line

& train by Tom Kraemer...

The Potomac Wharf Branch

[By Patrick H. Stakem] . . .

This is one in a series of short articles on the early mining railroads

of Allegany County, Maryland. These roads were built by the iron and coal

companies in the early 1840's, in anticipation of connecting with the B&O

Railroad and the C&O Canal, both then under construction to Cumberland.

Some of these standard gauge mine roads owned and operated their own equipment,

while others were operated with early B&O motive power and rolling

stock. By 1870, all of the lines were absorbed into the Cumberland & Pennsylvania

Railroad, which was itself absorbed into the Western Maryland system.

The Potomac Wharf Branch was built from Will's Creek, west of Cumberland,

by the Maryland Mining Company between 1846 and 1850, as an extension to

their Eckhart Branch Railroad. Will's Creek was bridged with a four-arch

structure built in 1849 (ref. 4), still standing in 1995. The Eckhart Branch

joined with the Mt. Savage Rail Road line on the west end of the Narrows.

After passing through the Narrows on the north (B&O) side, the Potomac

Wharf Branch recrossed Will's Creek on a bridge (no longer present) just

east of the present Rt. 40 road bridge. Some of the tracks may still be

seen near some billboards, and a gas station. Rail was removed from the

section west of the Valley Street crossing in Cumberland as late as 1990.

A classic wreck scene photo, circa 1860, shows the Potomac Wharf bridge

collapsed into Will's Creek, with engine C.E. Detmold dangling into the

creek. This image indicates the branch and the facility were in use at

least to this date. The original Potomac Wharf Branch bridge was a 203-foot

deck plate girder structure, with two support pillars in the creek. Built

in 1849, rebuilt after the Detmold accident, it survived until the flood

of 1936. The Potomac Wharf Branch was used to carry coal to flat-bottom

Potomac River boats, and to canal boats, before the canal wharf facility

was completed. The flat-bottom boats ferried coal down the Potomac to Georgetown

and Alexandria during the spring, when the water level was high enough

for navigation. After the C&O Canal reached Cumberland, canal boats

could enter the Potomac River via the guard locks. The original Potomac

River wharf had been built by John Galloway Lynn of Cumberland, and was

known as the Lynn Wharf. It was deeded to the Maryland Mining Company in

1852. There were a series of canal wharves. The Mt. Savage Railroad reportedly

built one in 1850. The 1923 ICC valuation docket for the C&P gives

the construction date for the concrete wharf as 1917. The B&O provided

access for the C&P to reach the Canal Wharf, charging a tonnage tariff

for this access. After the canal wharves came into common usage, the Potomac

Wharf was abandoned. Canal boats could also enter the Potomac River through

the guard locks, and proceed upriver for some distance. The dam in the

Potomac below the guard locks ensured that the Potomac was deeper at its

junction with Will's Creek than it is today. The guard locks and the dam

were removed as part of the Corps of Engineers flood control project in

the 1950s.

The Cumberland Coal & Iron Company, chartered in 1850, purchased

the Maryland Mining Company's mines and railroad in April 1852, including

the village of Eckhart. The railroad was operated by the new company until

1870. In that year, Cumberland Coal & Iron was itself acquired

by Consolidation Coal. The Eckhart Branch and the Potomac Wharf Branch

then became part of the Cumberland & Pennsylvania Railroad, also

owned by Consolidation Coal. Mellander (ref. 1) puts the length of the

Potomac Wharf Branch as 0.9 mile, and gives the river terminus as the position

where the present I-68 bridge passes over the B&O West End line. From

City Junction, where the Wharf Branch recrossed Will's Creek, the line

proceeded eastward to meet the B&O tracks at the southern end of the

B&O viaduct. The Potomac Wharf Branch was built to slope upward to

meet the B&O tracks at viaduct level. It crossed Valley Street, and

the south end of today's road bridge, at street level. The B&O line's

roadbed is some 20 feet higher than the Western Maryland line at that point.

East of Valley Street, some track and ties were still in place in 1994.

Looking back from the B&O line, the junction of the Wharf Branch is

easily seen. B&O"s Cumberland viaduct was built as a brick arch

structure during 1849-1851. The Wharf Branch line and the B&O main

passed through the "deep cut." The deep cut provides the West

End of the B&O with access to the Potomac River Valley towards Keyser

and Grafton. The viaduct passes over city streets, Will's Creek, and the

Western Maryland tracks (now used by the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad).

The viaduct is double-tracked, as is the deep cut. The southern end of

the cut is wide enough for triple track. The Potomac Wharf tracks were

on the west, but the wharf facility branched off to the east. The C&P

line merged into the B&O tracks, then crossed over to the easternmost

track. According to Price (ref. 6), the siding was 1000 feet long, extending

from Kelly Boulevard around to Will's Creek. The facility and method for

loading coal from the rail cars to the canal boats are not known. However,

it was probably not as convenient as dumping directly into the boats, as

was done with the later Canal Wharf facility. The Potomac Wharf was listed

on the C&P's ICC valuation sheets in 1918, although it is doubtful

it was in use at the time. Some rail and ties remained between the viaduct

and the Valley Street Bridge in 1994. That section of the line is built

on a raised section of land, with a reinforced retaining wall. The connection

has been removed from the B&O line, but the location is still visible.

The line was used into the 1940s as an industrial siding, serviced by the

B&O.

The Potomac Wharf Branch was an early intermodal experiment to provide

easy access for Western Maryland coal to the markets of the eastern seaboard.

Although its useful life was short, it provided needs short-term for the

export of the region's "black gold."

References:

- 1. Mellander, Deane, "Rails to the Big Vein, the Short Lines of

Allegany County, Maryland," January 1981, Potomac Chapter NRHS, Inc.

- 2. "Rail Tracks in Allegany County, Maryland," Book 1, 1980,

Preservation Society of Allegany County, Maryland, Cumberland.

- 3. Roberts, Charles S., "West End, Cumberland to Grafton 1848-1991,"

1991, Barnard, Roberts & Co., Baltimore, Maryland.

- 4. ICC Docket on C&P, dated 1923, in National Archives II,

College Park, Maryland.

- 5. Stakem, Patrick H., "The Eckhart Branch, 1846-1870," 1994.

- 6. Price, William, personal communication. [He remembers reading an

article in the Cumberland Times "100 Years Ago" column that gives

this figure.]

-

- Pat Stakem is the historian and a member of the board of directors

of the Western Maryland Chapter NRHS. He is a native of Cumberland, Maryland.

-

-

-