[By Allen Brougham] . . .

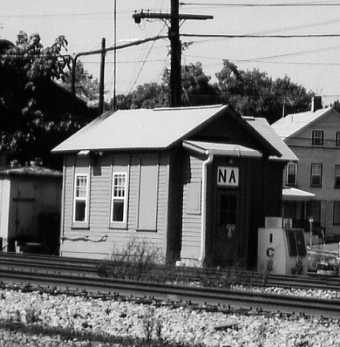

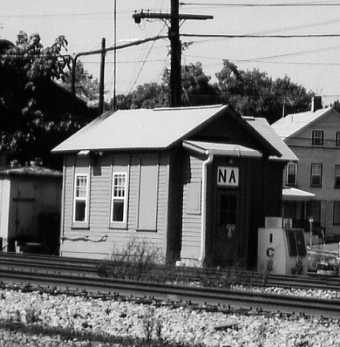

The century-old B&O interlocking office known as NA Tower in Martinsburg,

West Virginia, has closed. Its final day of operation was July 19 when

its signal control was removed, and the operators' positions were abolished

effective 7:00 A.M. on July 30.

The closing of NA Tower was part of a 23-mile switch and signal upgrade

on CSXT's Cumberland Subdivision between Sandy Hook, Maryland, and Pearson,

West Virginia. The project included the addition of three new control points,

the modification of two others, and the retirement of another. The names

of the five control points now in service along the affected portion of

track and under the jurisdiction of the 'CM' train dispatcher in Jacksonville,

Florida, are:

- Sandy Hook, milepost BA 80.5

- Harpers Ferry, milepost BA 81.3

- Shen, milepost BA 89.2

- Byrd, milepost BA 98.3

- Martinsburg, milepost BA 99.8

"Shen" is a shortened name for Shenandoah Junction, and "Byrd"

(location formerly called Rattling Bridge) is named for U.S. Senator Robert

Byrd (D-WV).

The project was actually the increment of a larger project begun in

the spring of 2000 to install a state-of-the-art electro-code signaling

system with higher-speed crossover switches along a 61-mile portion of

the Cumberland Subdivision as far west as Orleans Road, West Virginia.

An earlier increment involved the retirement of Miller and West Cumbo towers

in the fall of 2000. A later increment to include the retirement of the

tower at Hancock, West Virginia, is still in the planning stage.

Five operators' positions at NA Tower were affected. Four positions

were abolished, and the fifth position was modified to include custodial

duties at a different location to replace the single day that the operator

worked each week at the tower. The five operators owning regular positions

at NA Tower were:

- Carl Kief, first-shift

- Barb Eichelberger, second-shift

- George Speis, third-shift

- Patricia Reid, relief job

- Dick Campbell, rabbit job (one shift a week)

The affected operators will now exercise seniority onto clerical-craft

positions at other locations. Junior employees who are displaced will exercise

seniority in the same manner, with the prospect that furlough situations

could develop within several weeks as the process continues.

Second-shift operator Barb Eichelberger at the desk

at NA Tower about a week before the tower closed

With technological advances being the norm over the past several decades

and many railroads having been successful in retiring nearly all of their

interlocking towers many years ago, it was an anomaly that a cluster of

four towers spaced an average of a mere six miles apart within the Eastern

Panhandle of West Virginia would still exist until the fall of 2000. I

feel fortunate in having been a part of that scene. When I took a position

at Miller Tower in the fall of 1992, it was as though I were in a time

warp. Indeed, two of the towers - including mine - still controlled their

switches the old-fashioned way with armstrong levers connected to pipelines

to move the switches mechanically. When Miller Tower closed, I displaced

onto a position at Hancock Tower, which also used armstrong levers. It

still does. I retired in December 2000, but the tower at Hancock is still

in service. It alone survives the anomalous "cluster of four"

in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia.

It should be noted that the B&O Railroad was historically slow to

modernize its facilities. So when that company became included within the

umbrella of the Chessie System, there was a great deal of catching up to

do. Such was the case in November 1983 when Chessie's engineering and transportation

planning departments set a priority that the entire system would be equipped

with centralized train dispatching systems by the first quarter of 1989.

This included the need to retire all interlocking towers. Indeed, the then-Maryland

Division - whose territory included the four-tower cluster in the Eastern

Panhandle - was assigned the highest priority among eight affected divisions.

Start-up month on the Maryland Division was December 1983, with start-up

months on the other seven divisions ranging from March 1984 to July 1985.

Each division would have a target of about 13 quarters to complete the

project; the Maryland Division was slated for completion in the first quarter

of 1987. Thirty-two interlocking towers were listed on the Maryland Division

with 27 identified for elimination by completion date. It is unclear why

five towers were not identified for elimination at that time, but these

were eventually eliminated nevertheless.

While seven towers in the Baltimore area (which by 1983 had already

been funded for closing) were retired by the end of 1985, most of the remaining

towers identified for closing on the then-Maryland Division by the first

quarter of 1987 were still open at that time. This included the four towers

of the Eastern Panhandle cluster. When the Cumberland Sub project finally

began in the spring of 2000, it was planned that all four would be closed

by July 2001, with NA closing in May 2001. Only Miller and West Cumbo were

closed according to the 2000 plan; the increment involving NA Tower got

delayed for more than two years, and Hancock Tower still soldiers on to

this day.

In fact, with the closing of NA Tower at Martinsburg, four of the interlocking

towers of the entire then-Maryland Division identified in 1983 for closing

by 1987 are still open. They are:

- Brunswick (WB)

- Hancock (HO)

- West Keyser (Z)

- Rowlesburg (R)

Switch, Signal & Control Point Changes Resulting

From the Martinsburg Upgrade Project

Martinsburg Tower & the Blizzard of 1993

History of Martinsburg Tower

[Source: National Association of Railroad Passengers] . . .

1. Myth: Amtrak is unique in operating in the red, at taxpayers'

expense.

Fact: All transportation is subsidized by American taxpayers (see #2

regarding highways). Singling out Amtrak assumes taxpayers do not want

to invest in passenger rail. Polls consistently show that Americans support

federal funding for a national rail passenger system. A Washington Post

poll taken July 26-30, 2002 (and reported August 5, 2002), found 71 percent

support for continued or increased federal funding of Amtrak. Conservative

Columnist George Will, in a June 4, 2003, column, said the poll indicated

that "support for Amtrak is strong among all regions, ages, education

levels and income groups." A CNN/Gallup/USA Today poll conducted June

21-23, 2002 - near the height of Amtrak's funding crisis - found 70 percent

support for continued federal funding for Amtrak. Votes in Congress have

demonstrated time and again that taxpayers' duly elected representatives

agree.

2. Myth: Highways pay for themselves through user fees.

Fact: In 2001, 41 percent of funding for highways came from payments

not occasioned by highway use (i.e., property taxes, bonds, general funds,

other taxes and fees), according to the Brookings Institution's Series

on Transportation Reform (April 2003). The share of funding from these

sources has been growing. While most of this is at the state and local

levels, federal policy encourages this by offering states generous funding

matches for highway investments but no match for intercity rail investments.

3. Myth: Amtrak carries only a half-percent of the US travel market,

therefore it is insignificant.

Fact: Where there is a strong Amtrak presence, as in the Northeast Corridor

and New York-Albany, Amtrak dominates the airlines and offers a significant

alternative to automobile travel. (Amtrak handles about 50 percent of all

New York-Washington airline plus railroad traffic. This calculation includes

Newark/ JFK/ LaGuardia and Reagan National/ Dulles Airports; and these

rail stations: Stamford/New Rochelle/ New York/ Newark/ Newark Airport/

Metropark; New Carrollton/ Washington/ Alexandria/ Manassas/ Woodbridge/

Quantico/ Fredericksburg.) As travel volumes grow in the future, and construction

of new highways and airports becomes less practical, the need for such

services will around the nation. In rural areas, where Amtrak's infrastructure

costs are insignificant, Amtrak is often the only transportation alternative

to automobiles.

4. Myth: Private Freight Railroad companies subsidize Amtrak.

Fact: The freight railroads urged the federal government to create Amtrak

and agreed to provide access to their tracks at an incremental cost basis

in 1971. The case can be made for the opposite - that Amtrak subsidizes

the freight railroads. For much of Amtrak's existence, Congress prevented

Amtrak from contracting out work while the freight railroads reduced their

employment rolls (in some cases by contracting out), thus reducing the

amount freight railroads pay into Railroad Retirement. Amtrak workers are

"railroad employees." Railroad Retirement obligations - unlike

Railroad Unemployment Insurance payments - are calculated on an industry-wide

bias, with all companies paying the same rates. Therefore, Amtrak is subsidizing

the freight railroads' contribution to Railroad Retirement; Amtrak's "excess

Railroad Retirement payments" (about $150 million a year) is what

Amtrak contributes to Railroad Retirement for workers that Amtrak never

employed. If Amtrak were to go away, Railroad Retirement payments by the

freight railroads and their employees would be increased.

Also, capacity enhancements designed for passenger trains benefit freight

operations during much of the week. The newest example, with construction

just under way, is restoration of double-track on Union Pacific's mainline

just west of Sacramento.

5. Myth: Any dollar going to Amtrak is another dollar not going to

roads.

Fact: Federal funds for roads come from the Highway Trust Fund, a dedicated

long-term source of funding, whereas Amtrak receives federal dollars from

the General Fund through the annual appropriations process. However, states

and local governments should have the option to spend transportation dollars

on the most efficient mode of transportation. Current policy discourages

states and local governments from investing in intercity rail.

6. Myth: Shut down Amtrak and the private sector will operate passenger

rail.

Fact: Rail passenger service was in private hands from its inception

in the 1830s until 1970, when Congress and the Nixon Administration made

a policy decision to create Amtrak because the private sector could not

make a profit. The private sector operators that have expressed an interest

in operating rail passenger service will do so for a fee with the clear

expectation that the government will absorb the associated losses. Furthermore,

most Amtrak route miles are on tracks whose owners, the private freight

railroads, do not want to run their own passenger trains and have a top

priority of opposing legislation to give Amtrak's rights (for track access

at reasonable cost) to any other entity. The practical result of shutting

down Amtrak would be elimination of intercity passenger rail.

7. Myth: Flying is cheaper than taking a long-distance train.

Fact: Anyone with a computer can find a train fare that is less than

an airfare, or the opposite. Long-distance trains don't just go from one

major market to another like flights, but serve many intermediate markets

with poor air service (or no air service, or costly air service). Furthermore,

the walk-up fare for an Amtrak trip is often much less than walk-up airfare.

There are also people who cannot or do not want to fly.

8. Myth: One particular route (e.g., the Kentucky Cardinal between

Chicago and Louisville) shows the entire national system is flawed.

Fact: The Kentucky Cardinal was instituted in 1999 to grow express package

business. The profitable business never materialized and Amtrak discontinued

the route on July 6, 2003. Despite limited ridership, no community wants

its passenger train to disappear. Residents of Louisville recently filed

a class action suit against Amtrak and the USDOT to bring back the route.

9. Myth: The overwhelming majority of Americans have chosen the automobile

lifestyle.

Fact: To a large extent, this apparent "choice" reflects a

necessary response to pro-highway federal policies, which for decades have

encouraged state and local decisions that foster reliance on the automobile.

States - naturally influenced in choosing transportation projects by the

federal funding available for those projects - can obtain generous federal

matches for investments in highways-often 80 percent and 90 percent of

a project's total cost-and aviation, but there is no federal match for

states to develop intercity rail projects. The public's interest in more

travel choices is reflected both in the aforementioned polls and in ridership

increases on Amtrak over five straight years (Fiscal 1997-2001) and on

mass transit. At a June 27, 2003, conference on traffic congestion, American

Public Transportation Association President William Millar stated: "Since

1995, transit ridership has grown by 21 percent, versus 16 percent for

driving and 12 percent for domestic airlines. More people are taking public

transportation now than in the last 40 years." Also, on April 17,

2001, The Washington Post reported, "Mass-transit ridership grew faster

than highway use for the third year in a row last year, according to new

national figures."

10. Myth: Amtrak labor protection is outrageous.

Fact: Labor protection flowed from the railroad industry and the creation

of Amtrak by Congress. Railroad workers historically have had strong labor

protection. At the major freight railroads, protection can be triggered

by many more events than at Amtrak. This was true even before Amtrak labor

protection was scaled back as a result of the 1997 Amtrak reauthorization

law.

Labor protection has no impact on day-to-day operating costs. It only

comes into play when a route is discontinued or a mechanical facility is

closed. In other words, none of the 1,000 employees Amtrak laid off in

the past year got labor protection. Even when a facility is closed, Amtrak

can avoid labor protection simply by letting employees follow their work,

and - for employees who choose to do that - paying moving costs.

In the last reauthorization in 1997, rather than repealing labor protection

provided by law outright, Congress sunset the provision, subject to negotiation

of a substitute labor protection provision by the unions and Amtrak under

the provisions of the Railway Labor Act. The result of those negotiations

was an arbitration award which reduced the benefits of labor protection

for Amtrak employees.

Looking more broadly at Amtrak labor issues, many Amtrak pay rates are

less than for comparable work at commuter railroads and some other companies.

Commuter railroads and electric utilities benefit from "Amtrak as

training ground," using higher pay to attract Amtrak employees.

- Linemen (who work on overhead electrification) get about $20 an hour

at Amtrak but $33-$35 at Newark-based Public Service Electric and Gas Company.

Pennsylvania Power & Light Inc. recently advertised positions at $30

an hour.

- Commuter rail examples: Locomotive engineers' hourly rate is $27.24

at Amtrak, $29.92 at Long Island RR, $25.73 at New Jersey Transit. The

trackman rate is $16.31 at Amtrak, $19.03 at Metra (Illinois), $20.42 at

SEPTA (Philadelphia), $23.33 at Long Island.

Gunn has made clear his belief that Amtrak pay rates are not excessive,

and that the primary focus for Amtrak management in labor negotiations

will be productivity and medical cost containment issues.

Unlike many employees in the private sector, Amtrak employees have never

benefited from stock options.

Meanwhile, Amtrak management - which does not get labor protection -

has not had a general salary increase since Fiscal 1997 (lump sum payments

FY 1998 and FY 1999).

- NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF RAILROAD PASSENGERS

- 900 SECOND ST., N.E., SUITE 308

- WASHINGTON DC 20002-3557

- Prepared July 10, 2003